These days, I find myself walking through burial sites, thinking about those who have gone before, wondering about the faces and lives of those whose names line the monuments and markers of these sacred places. I was not always this comfortable with the things of the dead and death. I was taught to be afraid of death, dying, funerals and burial places. Cemeteries and funerals were not happy places, what’s more, there was a mystery that shrouded death and said that children should stay away.

These days, I find myself walking through burial sites, thinking about those who have gone before, wondering about the faces and lives of those whose names line the monuments and markers of these sacred places. I was not always this comfortable with the things of the dead and death. I was taught to be afraid of death, dying, funerals and burial places. Cemeteries and funerals were not happy places, what’s more, there was a mystery that shrouded death and said that children should stay away.

I remember the first funeral I attended. I remember the first time I saw a casket or was close to a person who died. I remember watching someone take her last breath. I was not ready for her death and even less ready for her funeral. Hers was the first body I saw in a coffin, the first occasion I had for attending a funeral, for being in a place where people are buried. Her death was a time of fear in my life: fear of things I could not explain, fear of a God who did not answer my prayers and let her live, fear of death and what the afterlife would be.

Now, I have fewer questions about death and dying. I no longer wonder why some live and some die. I have seen the young die unexpectedly, and watched the graceful aging of those who were expected to die. Death is as much about a past that is lost in hope, as it is about a future that appears selective and at times uncertain. Any rumination I have about death is no longer rooted in fear, but is framed in reconciling the past with the present, as I long for a future full of hope and well-being for all people.

A part of my new attitude comes from my visits with the Ancestors. These are no longer “dead people”, skeletons to be feared, or ghosts that haunt and frighten, instead, those who have gone before are a wealth of wisdom and a well of Divine grace and light to be visited and honored along the way. I walk the burial places that I encounter, reading the markers along the way and noting the differences in places where bodies are laid to rest in death.

I “visited” my grandparents in Jamaica and explored their burial site in the rear of the Golden Grove Methodist Church in Higgins Town, St. Ann. They are enjoying their rest, side-by-side under a beautiful shade tree undisturbed. Her grave has a head stone with her name, his does not, but I know where to go to find them. There are a few other relatives in that place too, a quiet place where I would hope, they will remain undisturbed. But what of the other Ancestors? The older Ancestors, the enslaved Ancestors? The indigenous? Where are they buried? Are they still resting or have they too become foundations of buildings and courthouses from which they watch their descendants being walked through those halls in bright shiny shackles and chains?

In the past months, I have visited these places where the Ancestors have been placed in the ground, places where they know no rest. Why are some people buried in “cemeteries” while others are in “burial grounds”? Why are some places sacred, while others have been visited by bulldozers and back hoes to make way for residential buildings and court houses? In life as in death, some endure invisibility and disrespect.

These questions of whose resting places are left undisturbed first came to me when I visited the African Burial Ground Memorial. In the blog post I wrote, Hiding in Plain Sight, I chronicled some of my lament over the monuments and ways some are memorialized over others. How can a 6.6 acre burial site – a sacred resting place for the dead – give way to government buildings and courthouses? How can people who were brought in chains and bought on auction blocks be a part of the foundation of the Immigration Building and the Federal Courthouse in Manhattan? There is an irony here that even I am not equipped to engage.

Meanwhile over at the Trinity Episcopal Church and Wall Street where the hands of enslaved Africans laid the foundations of churches and gave sweat and tears to the wealth of the growing United States, a place for burial was denied. The burials at Trinity Church did not include the enslaved Africans and their descendants, those who were laid to rest in barely marked graves because open celebration of their lives and grieving of their deaths was outlawed. Where is the dignity afforded the dead?

According to the dictionary, there is no difference between a cemetery and a burial ground: a cemetery is defined as a burial ground, and a burial ground is a cemetery. However, somewhere along the way these words have become radicalized in a very subtle way. The burial sites of Indigenous Peoples, African peoples and their descendants became “burial grounds” particularly in places where they were not allowed to be buried in the cemeteries that were reserved for burying Whites. Because these sites were not viewed as “cemeteries” it was easier to remove them, even in places where they were known to exist. I would also name that these burial sites were often in remote places and unmarked which further adds to the naming, recognition, and saving of these sites.

All burial sites are sacred resting places for those whose lives were valued and whose death are to be remembered. Value of life is the hidden factor even in the naming of burial places – resting places for the dead. I have a hard time using the word cemetery these days, when I live with the knowledge that my forebears were not considered valuable enough to have their burial sites deemed “cemetery” or valued enough to be laid to rest with dignity and respect in the same way their oppressors and enslavers were treated. All of these places are now “burial grounds” to me.

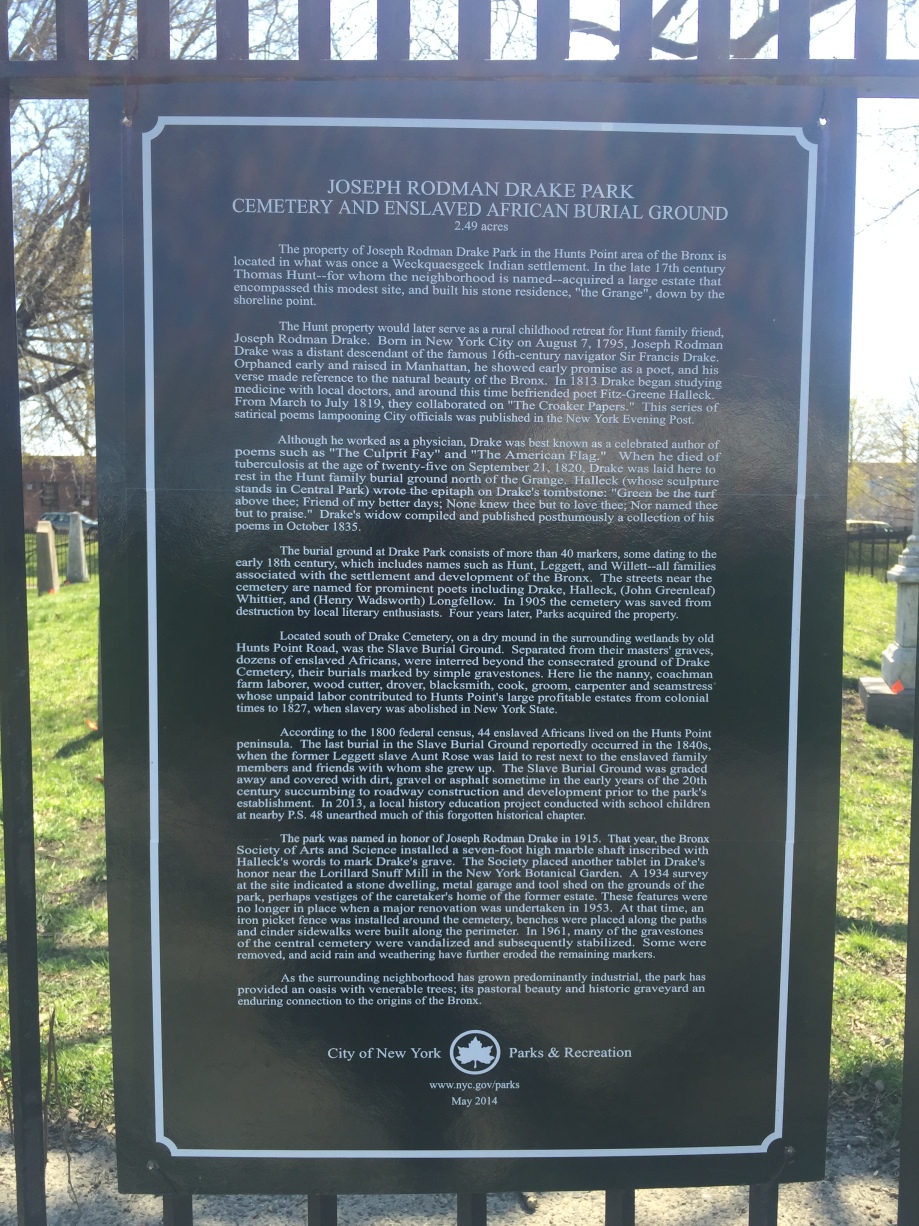

These lands, were also a part of the Weckquaesgeek Indian settlement in the 17th century. The Hunts, Leggets and Willetts are buried in this burial site, their head stones in tact, their resting places surrounded by a large wrought iron fence to keep them in. These are some of the families who helped to “develop” the Bronx. I wondered what and how they did that, because the marker on the fence was rather vague. And then, there it was, in the sixth paragraph, three paragraphs up from the end to ensure that only the patient and persistent would know:

Located south of Drake Cemetery, on a dry mound in the surrounding wetlands by old Hunts Point Road, was the Slave Burial Ground. Separated from their masters’ graves, dozens of enslaved Africans, were interred beyond the consecrated ground of Drake Cemetery, their burials marked by simple gravestones. Here lie the nanny, coachman, farm laborer, wood cutter, drover, blacksmith, cook, groom, carpenter and seamstress, whose unpaid labor contributed to Hunts Point’s large profitable estates from colonial times to 1827, when slavery was abolished in New York State.

According to the 1800 federal census, 44 enslaved Africans lived on the Hunts Point peninsula. The last burial in the Slave Burial Ground reportedly occurred in the 1840s, when the former Leggett slave Aunt Rose was laid to rest next to the enslaved family members and friends with whom she grew up. The Slave Burial Ground was graded away and covered with dirt, gravel or asphalt sometime in the early years of the 20th century succumbing to roadway construction and development prior to the park’s establishment. In 2013, a local history education project conducted with school children at nearby P.S. 48 unearthed much of this forgotten historical chapter.

These too were slave owners buried and past and somewhere in the vicinity was the burial site for the enslaved people who could not be buried with their owners. It was the children of PS 48 (I called but no one returned my message) who found the site and placed the marker in the park to honor the African ancestors who were buried close by. The resting places of these Ancestors were now the paved asphalt streets of Hunts Points and the foundation of the industrial buildings that line the streets. And in a shady park, at the corner of Hunts Point and Oak rest their former owners protected, their memories and names preserved by the New York Parks and Recreation Department.

I left Hunts Point disappointed that once again that Black lives were forgotten, sacred places trampled and the resting places desecrated for so many.

Where are the many enslaved people who came to these shores and the Caribbean and the rest of South America buried? The Atlantic Ocean and its seas are a huge burial ground where those who did not survive the middle passage rest. I wonder where the bodies of the African residents and their descendants who worked the Van Cortlandt plantation and other plantations of the Bronx now rest. Where are the remains of those who fled to Brooklyn and other parts of Manhattan? What of other parts of the United States?

As the rest of the group made their way in one direction, I headed back in the direction from which we came, making my way to see and to visit, if only for a moment. And there it was – the sign under the tree. A hand written marker for the many unnamed who once perhaps were a part of the plantation whose “big house” was down the dirt road and across the street. This place was sacred. In that clearing, I met the Ancestors, acknowledged them and though unnamed I know them, because they live on the air I breathe and they speak on the whispers of the breeze in the trees.

And my heart broke some more that day, for what we do not know and choose not to remember. I wept, for the many places that are sacred that get trampled beneath our feet, with no sign to guide us, because we choose not to see the signs that are everywhere around us. I was the only one who went back, the only one who owned the significance of the sign on the road that day.

I now think about the places I visit from a different perspective, and more so the places where my feet tread. Ever wonder what was on the site you now know as the current high-rise, present home, local street, school or hospital? Somewhere in the fields of our parks and the streets of our cities are names and stories paved and built over, no marker to remind that the sacred is among us. Perhaps we need to create space for pause and silence in the midst of our busy lives to remember those who are among us, silent, unnamed, but not forgotten.

I scheduled this post for posting on this Monday. It was more than 24 hours later that I realized that it will post on Memorial Day, a day when we honor the dead, particularly those who have fought in war. And then I saw the New York Times article about Memorial Day and its history. A part of that article read:

The war was over, and Memorial Day had been founded by African-Americans in a ritual of remembrance and consecration. The war, they had boldly announced, had been about the triumph of their emancipation over a slaveholders’ republic. They were themselves the true patriots.

May the Ancestors rest in peace. May all burial sites be called Sacred Places! May we continue to find and memorialize these sacred places of the Ancestors.

Thank you for this powerful reminder, especially on this Memorial Day, to “create space for pause and silence in the midst of our busy lives to remember those who are among us, silent, unnamed, but not forgotten.”

LikeLike

Thanks for reading Melanie

LikeLike

Beautiful reading for Memorial Day. It reminds me of a post I just read about a project that is placing floating headstones in the sea to create a “burial ground” for the Syrian refugees who have drowned on their journey out of harms way. Of course, they all have names….

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Anne. Yes, they all have name.

LikeLike

Thank you so much for this wonderfully heartfelt and meaningful posting. you have touchedmy soul with your writing.

LikeLike

Thank you so much for sharing your experience. This has helped me to understand why I am drawn to the places of the dead. I remember the burial site of my grandparents on the side of the road in Ahoskie N.C. markers barely readable. So many I wish I knew but know that no one knows where they are. There are no funeral programs,obituaries or video. I only know it in my heart that they were.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And for that and so many reasons we must remember and keep them in our hearts and on our lips

LikeLike

Black lives matter even in death; especially in death. The irony.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Indeed!

LikeLike

Reverend, thank you for this re-minder. As a veteran, I appreciate every remembrance of our ancestors and our veterans. Most graciously, Chaplain Pj! AKA Wisdom.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Rev.

LikeLike

I love this! Thank you for reviving the reconciliation of past, present through the inevitable.

LikeLike

Thanks for reading Kai

LikeLike

I have a hard time with words to respond to the evil and pain you evoke, and am grateful for the hope you evoke as well. I’m struck forcibly with the difference in the assumptions I can make about my ancestors’ burials and those that you reflect for black people. Racism is a stream flowing through our history – really a rushing torrent. Thank you for reminding me, again, to be always aware. Thank you for letting us see and hear what you are seeing and thinking.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for reading And for your thoughtful reflection

LikeLike

There is a deep human need for life to have meaning. When we treat others as a means to our ends, we see no other meaning in their lives. You are reclaiming communal meaning in the lives of those who went before. It is a holy journey and a blessed task!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Sandy

LikeLike

Thznk you very interesting stories

Itsa shame ,yes there is no respect for the dead, anymore”people become materialistic ,so the ordinary people are not even history , their resting place are of no value to the living .

The living human are becoming , preditors to wild life and our enviroment ,very distructive ;there is a word pronounce development if one bed is in hell they will be didtroy in the interest of mans plan , so our dead will never escape .

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Mazielyn

LikeLike

Karen Georgia has given us yet another opportunity to ponder the past and its implications for the present. For much of my life, Memorial Day has been much more about the “great cloud of witnesses”, the ancestors, than it has been about those lost in war. This is not to say that those lost in war are not important. They are worthy of the honor accorded them. However, there is more to be remembered and Karen reminds us of the many who are forgotten, whose names are unknown, but whose lives were lives of struggle and survival in the midst of a brutal system of enslavement. Their forced labor laid the economic foundation for this nation and built many of its earliest edifices. (Consider Washington, DC.) For that alone, and so much more they must be remembered.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Geoffrey

LikeLike

The words were powerful, and so were the pictures. i was in Washington DC this week, in the Anacostia section of the city, near where my parents are buried — in a black cemetery because until the 1970’s blacks and whites were not buried together in our Nation’s Capitol. Isn’t that sad?

LikeLike

This:

“According to the dictionary, there is no difference between a cemetery and a burial ground: a cemetery is defined as a burial ground, and a burial ground is a cemetery. However, somewhere along the way these words have become radicalized in a very subtle way. The burial sites of Indigenous Peoples, African peoples and their descendants became “burial grounds” particularly in places where they were not allowed to be buried in the cemeteries that were reserved for burying Whites. Because these sites were not viewed as “cemeteries” it was easier to remove them, even in places where they were known to exist. I would also name that these burial sites were often in remote places and unmarked which further adds to the naming, recognition, and saving of these sites.”

The truth of this sank into me.

LikeLiked by 1 person